We often refer to “the huntbooks” when we write our texts. These are books about hunting written in the middle ages. In the 14:th Century there is mainly three books that concern us, they are also the most well known of all the medieval huntbooks. There are other prominent huntbooks from other centuries, the most important here being The Art of Venery,1327, by the Anglo-French Master of game, Twiti (Twici). Many of the later books draws on this and it is probably the basis of the ones we use the most. Sadly it has yet been unobtainable for us.

The books we use the most are instead;

Les livres du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio (1354–1376), attributed to Henri de Ferrières

Livre de Chasse (1387–1389), Gaston III (Phėbus) Phoebus, Count of Foix. Various copies with excellent illustrations. Also known as Book of The Hunt.

The Master of Game, Edward, Duke of York

Lets take a closer look at them and how they relate to each other….

Les livres du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio

Les livres du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio or, the book of king method and Queen Theory. This book is attributed to Henri de Ferrieres and it is said that after the big plague in the 50:ies people where concerned that so many had died that knowledge would have died with them. Therefore they set the art of the hunt to text. The second part of the book also contains ‘the dream of the pestilence’. It is written as an allegory where King Modus or Queen Ratio answers questions posed to them. There is also a fair amount of moral and musings about the religious thinking concerning the hunt.

Henri de Ferrieres

The probable author of Les livres du roi Modus

et de la reine Ratio is Henri de Ferrieres. There are some possible persons this might be. The most probable was born in the first decades of the 14:th century. in 1347 there is a note about a Henri de Ferrieres being a captive of the English. In 1369 a Henri de Ferrieres is reported as being commander of the fortress Pont de l’ Arche. The Ferrieres owned the Breteuil forest north of Paris, a forest mentioned in the book. The author also say he saw Charles IV hunt as a child. So it seems he was a man that was an active part of the hundred years war. A thing that is verified in some parts of the book (the dream of pestilence is insightful and refers to tactical situations in 1374)

King of pratice

This book is one of our favourites since it is very good at explaining things. There are several copies (21 copies is known) ranging from 1380 to 1486. This means that the book was popular and recopied for a long time. The copies we use is mostly Paris 1 for pictures, the oldest existing copy. We also use the Copenhagen ex as this is translated into Swedish and interpreted by Gunnar Tilliander, considered one of the best in Medieval French of his time. It has very nice illuminations showing a wide range of hunting.

Livre de chasse

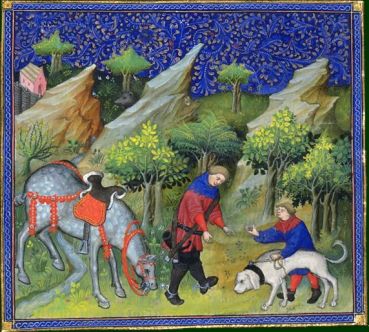

Livre de chasse is possibly the most well known of all huntbooks. No small part of this is that some of the copies sports beautiful, detailed, illuminations (illustrations). It is written in 1387-89 and exists in 46 known copies. The most well known and used are the copy in Musée national du Moyen Âge, Musée de Cluny from 1407-10 (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris Ms. fr. 616) and the Morgan library copy, also from 1407.

Gaston Phoebus

Livre de chasse is written by Gaston III/X of Foix-Béarn. He is more known as Gaston ‘Phoebus’, Phoebus being another name for the Greek god Apollon, and Gaston being known for being a very handsome

man which earned him this nickname. He recorded the three “special delights” of his life as “arms, love and hunting”. Jean Froissart, the author of “Chronicles de France” visited his Court in Pau and was impressed with its splendour. Gaston was born 30 of April in 1331 and died while washing his hands after a bearhunt in 1391. He had a son, but he stabbed him to death in a quarrel after the son had tried to poison him. Another of his sons, illegitimate, was one of the poor souls that died in the infamous Bal des ardent

Gaston was widely acclaimed to be a great hunter and

even travelled to the far Sweden to hunt reindeers, possibly in connection to when he was fighting pagans in Prussia. He also fought in the Hundred years war, so it is quite possible he met Henri de Ferriers in person.

Book of the hunt

Livre de chasse is an excellent book, but hard to get hold of a copy as it only exists in French and that is a language I am regrettably bad in. The pictures are very good though and very informative. As the Livre de chasse follows King modus in its layout many of the pictures can get explained in other versions. Also, the Morgan library has some nice informative text abstracts. We use the Morgan library and the French one mostly.

The master of game

The master of game is a English translation of Livre de chasse made in between 1406 and 1413 of Edward of Norwich. He also added some new chapters of his own and edited it for English hunters (for example he skipped Gastons descriptions of reindeers as he did not think it had any relevance for an English audience)

Edward of Norwich

Edward of Norwich was born 1373 and is also known as Edward of Langley. He was the second Duke of York. He took a prominent part in the hundred years war and served there under both king Henry IV and Henry V. He also took part in some important emissaries to the French Court, amongst one in negotiating the wedding between Henry V and Catherine of Valois. When he was there Gaston Phoebus was already dead, so the chance that they met might have been slim. Edward was only 18 when Gaston kicked the bucket (presumably, as he was washing his hands at the time of his demise). Edward partook at the siege of Harfleur and commanded the right wing at the Battle of Azincourt. At Azincourt he became the highest ranking casualty when he met his fate on St. Crispins day.

Has also was, and this is more to our point, the master of harthounds for Henry IV.

The book

The master of game is a good book, but it is abit more amateurish in appearance then Livre de Chasse and King modus. It is written in a straightforward and matter of factly way. Even if there is some passages that are somewhat rambling in nature. Some parts (the ones Edward was not interested in) is put forward to others (he directs the hunting of otters to the kings otterhunter). For example he does not go into the disembowling of the animal as he say this is more of a woodsmans discipline then a hunters. It has some translation errors from Gastons original, but I think it deserves to be judged as a book of its own. It is after all written by a master of harthounds and therefore an experienced hunter. He would not put anything in there that he did not agree with (indeed there is some alterations to fit English hunters). There is a edition of this book with a foreword by Ted Roosevelt from 1909 that holds a high class. The appendix in the book is a very good read to get started with the medieval hunt. It exists in a on-line version here. I have not seen any pictures from this book.

The books amongst themselves

As we can see the Les livres du roi Modus et de la reine Ratio is the first and the one that sets the trend in what a huntbook should contain. Gastons book follow the same pattern, but is more direct in its tone and the Master of hunt is, of course, like Livre de chasse. But all books are written by active and highly valued hunters. We can be fairly sure that what they write is things they agree with and condole the practise of. Edward writes in some places about how things are done, and that he does not think it is good. This shows that he knows what he is talking about (or at least thinks so). Many medieval books are written by clerics that do not always have the practical experience of what they are writing about and therefore might not show a correct description of the actual practise used in the middle ages.

Books of the middle ages where copied by hand. This meant that errors was made. When a copy was copied the error was duplicated, and more errors might occur. This results in that often the book closest to the original is the most accurate. It is good to know what copy it is you are working from, and preferable to know how far removed from the original it is.

How we use manuscript sources.

WE use the manuscripts both as written sources detailing how they where thinking about the hunt and how it was conducted.

We also use the illuminations (pictures) as a source for equipment. These hands on books are very good in a interpretation viewpoint. We don’t have to guess what the pictures show and if it is allegorical or not. The text is explaining the pictures (and the pictures the texts). When you do not have the text available, you can often use the text from another book. As they deal with mostly the same you can identify the stages of the hunt as long as you know the other texts. Correlation between the texts can be done to see changes in the hunting equipment. It is harder to see changes in tactics as you do not know if these show individual preferences or a common overall change. Pictures can be used right as they are, to ensure you get an outfit of a hunter consisting of clothes that was actually worn together. Not to easy to know for modern people and could result in what would be in modern day someone wearing shorts and tuxedo.

In conclusion

The huntbooks are very fun to read. They are hands on and often rather funny. If one is interested in the hunt it is often a revelation to read them. Getting explanations to odd looking pictures one have gleaned on the wide interwebz. With such good books, and easily obtained, on a subject I would say that it is very hard to try and reenact the hunt without reading at least the master of game or looking at the excellent illuminations of the Morgans copy of Livre de chasse. If you read those you might even be able to base a whole blog on them….

/Johan

Hi,

Just in case that you are still looking for Twiti’s text, below a link to a book from 1843 with the original text and an englisch translation on google books:

https://books.google.de/books?id=xZVkAAAAcAAJ&pg=PA11&dq=the+art+of+hunting&hl=de&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwiDvauQ5c3NAhUEbRQKHVbgDzoQ6AEIMzAD#v=onepage&q=the%20art%20of%20hunting&f=false

Best regards from Germany

Jörg / Henneken dem Weydemanne

Oh, thank you. That is very helpfull!

Pingback: The hunt | Exploring the medieval hunt

https://archive.org/stream/masterofgameo00edwa#page/18/mode/2up

The Master of Game is now available online in all its glory (the 1909 English translation). It also has the illustrations too!

Pingback: The Unicorn Defends Itself | J.M. Ney-Grimm

please give me information about the medieval hunting boots in Master of the Game that button or lace on the sides or were they attached to leather leggions?