In the olden days everyone wore hats! A man would not show his face outside hatless. This is an often repeated “fact” one hear about the medieval times.

Except that it is not true.

In this article I will look a little on the lid. How it looks in sources, and how it does not look. I will make my pardons before hand, as i will point at some things that i see reenactors commonly do. Those that does, will feel that I am attacking them personally, but I am not. You are totally free to do as you like with your hatting, but I have chosen this way to share my theories. Once they are out there you can take them or leave them as you please. I will paint with a broad brush here. Talking about generals. You can always find an exception. And that’s good. Exceptions needs reenactor love to. As always the article mostly looks at later 14th century as this is our main focus.

So lets start with issue nr one, and work our way down my peeve list.

Hat or no hat

When you look at pictures, lets say pictures of hunters, just to keep with the subject of the blog. Hunters are mostly outdoors, and they are doing outdoorsy stuff. Ergo, this is a situation where you, as a man, would have used a hat. Just to be decent. But, if you look at pictures, at least half of them, sometimes even more, are having no hat, or hood. This is also a trend in other, non hunting, manuscripts. So, going around hatless (and i mean bare haired, not with a coif) is totally ok in most cases. I do that at times, just to even out the numbers of hat vs. no hats.

Feathers in the hat

Feathers in the hat is way over represented in medieval reenacting. We

are not fully sure what a feather in the hat means, if it means something. Perhaps it is just there to be pretty. There are some indications that they might denote someone that is charge of something. Like a symbol of authority.

Preferred feathers seems to be imported  ones. Ostrich, parrot, peacock

ones. Ostrich, parrot, peacock

and other rare and exotic feathers was shipped around and dyed.

When looking at the placement of these feathers they are almost exclusively placed at front center of the hat. In a few cases in the back center. Placing at the side of the hat is virtually never seen (at least in comparison to front center). The feather was in most

cases placed in a fancy featherholder.

Badges and decorations

Reenactors love their badges. The more pornographic the better.

These ‘carnival badges’ are a conundrum. We know they existed and was fairly popular due to the amount of them we find. We have no real idea of how they where worn though. Some believe they are temporary badges. Made and sold for an event and then thrown away. Like.. a Carnival. They are not shown in illuminations and not mentioned in texts. And one place they are never seen… is on hats.

The only badges seen on hats are on pilgrims on an active pilgrimage. If you Reenact one of those, you are spot on to sport a couple of badges you have proudly earned (in our group you are not allowed to wear the pilgrimbadge unless you have made the pilgrimage and heard mass there, but that is just our own rules) .

If you are not reenacting a pilgrim.. well, let me ask you this: Have you seen a hat with badges on in those cases?

There are some decorative ‘badges’ in hats though. These are not the tin penis kind, but more jewelry like brooches with pearls and gold. Sported by the rich to show off (and to look pretty).

There are some decorative ‘badges’ in hats though. These are not the tin penis kind, but more jewelry like brooches with pearls and gold. Sported by the rich to show off (and to look pretty).

Gothic Cast makes lovely brooches that fits upscale hats, if you like to get one.

Embroidery

There are several pictures of what seems to be embroidery on hats. These are mostly lines, straight and wavy and circles and dots. This is rarely seen on reenactors, so there you have a niche you can fill!

There are several pictures of what seems to be embroidery on hats. These are mostly lines, straight and wavy and circles and dots. This is rarely seen on reenactors, so there you have a niche you can fill!

Another kind of embroidery is applications and/or intarsia embroidery. They seem less common but you can see them at times.

- I am adding a little disclaimer here.

There are some discussion that the above hats show depictions of fur. This might very well be true. The reason we have chosen to believe that this is not the case in these cases is that Lorenzetti has a very naturalistic way of painting and that fur is mostly depicted ‘as is’ in his works. This is more reminiscent of stylised fur, like you might see in a simpler rendition,like say the Manesse codex. So, it does not fit the style of painting to have a stylized fur in these pictures….but it certainly is possible.

The coif

The coif, that i like to see as the underwear of the head, is hardly ever seen after the mid of 14th century. If it is, it is mostly on antiquated gentlemen that are stuck in the fashion of their youth… When they are used, their bands are tied. Unless you are Dante Alighieri. Are you Dante Alighieri ? (and that painting was painted more than 150 years later… what did they know about coifs!)

These… are my thoughts about hats. The fancy hat has spoken.

Like hats?

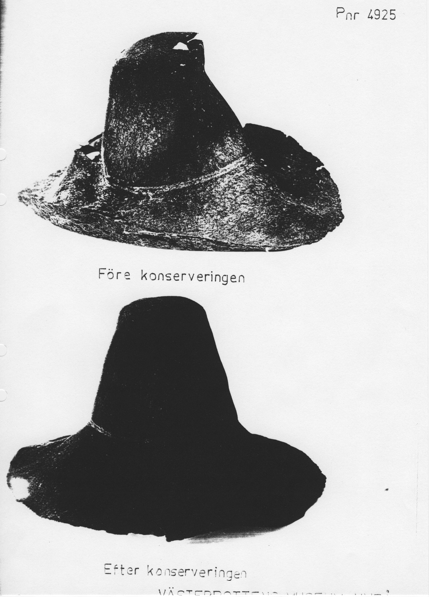

Check out this article about a very well preserved 14th century swedish hat.

Also, dont miss THIS article about knitted hats in 14th century