It is now time to take a look on what tools was thought to be needed for handling the dogs during the middleages. This article will concern mostly late 14:th and early 15:th century, but some offshoots might occur to other times. Like always we lean heavily, or maybe all on, the tools used in the hunt. We will use archaeological finds, textual evidence, illuminations and sculptures to get into the nuts and bolts of the medieval doghandlingtools and how they where used. Words and meanings of expressions you can get an explanation to in the article about the medieval dog, here. The use of the words ‘dog’ and ‘hound’ is here used in the medieval way, where there was no bigger distinction between the two. The both meant rather the same back then.

It is now time to take a look on what tools was thought to be needed for handling the dogs during the middleages. This article will concern mostly late 14:th and early 15:th century, but some offshoots might occur to other times. Like always we lean heavily, or maybe all on, the tools used in the hunt. We will use archaeological finds, textual evidence, illuminations and sculptures to get into the nuts and bolts of the medieval doghandlingtools and how they where used. Words and meanings of expressions you can get an explanation to in the article about the medieval dog, here. The use of the words ‘dog’ and ‘hound’ is here used in the medieval way, where there was no bigger distinction between the two. The both meant rather the same back then.

The man handling the dogs where called a ‘berner’ or ‘Valet de chiens’. If he was the one using a limer he was reffered to as ‘lymerer’. The berner in charge of greyhounds was sometimes called a ‘feweter’ or ‘veltrahus’ in gallo-latin. Needless to say, doghandling was something that was though of as a craft. The doghandlers where supposed to memorise the names and characteristics of the dogs, hear in the way they bayed if they where on the track, had lost track, or where standing the game.

Collars

A copper ornament from Waterford, Ireland. A dogcollar from 12:th cent, probably riveted onto leather

The collars of the middleages where sometimes highly decorated. Showing the high value you put on the dog. The more run of the mill collars where simpler, but it seems that leather and textile are the most common. There are also special collars for different purposes.

♦ Regular collars In illuminations (medieval book illustrations) most collars are red with golden studs. Some blue, black and one or two green also appears. Most probable these are made out of leather, but some might as well be textile. Most seem to be of the non choke kind, and uses one buckle to close it.

In illuminations (medieval book illustrations) most collars are red with golden studs. Some blue, black and one or two green also appears. Most probable these are made out of leather, but some might as well be textile. Most seem to be of the non choke kind, and uses one buckle to close it.

Other kinds of collars seems to use two buckles and a swivel for the leash between them. finds of the buckles and swivels are sometimes made. They can also be seen on illuminations and paintings.

In Q. R. Wardrobe Ace. for 1400 is mentioned “2 collars for greyhounds (kverer) le tissue white and green with letters and silver turrets.” also, one of ” soy chekerey vert

et noir avec le tret (? turret) letters and bells of silver gin.” in Expanses of Queen Mary is also mentioned ” Dog collors of crymson vellat with vi lyhams of white leather.”

♦ Wolfcollars

Wolfcollars are collars with big spikes protruding from them.

The purpose of these are that the wolf should not be able to close its jaws over the throat/neck of the dog. The spikes do not have to be sharp for this, but many wolfcollars have very sharp spikes indeed. These collars was worn by dogs hunting wolf. Also, and maybe more common, they are worn by dogs guarding cattle or sheep against wolves.

Some common wolfcollar seems to have been made of linked metal-chains with spikes. These may, or may not have been backed by leather.

Collar from Vendel in sweden. Possibly a wolfcollar, the spikes have eroded somewhat. early vikingage

Others seems to have the spikes fastened on a leather or textile collar. I choose to make one of the leather versions, backed with several layers of canvas. To stop the spikes from being pushed backwards and chafing the neck the canvas was stitched in ‘compartments’ around the spikes. The spikes themselves are roughly forged on just an anvil and have large flat heads.

♦ Mail/scales collar?

There is some uncertainty around the use of mailcollars to protect the dogs. These would predominantly have been used in boarbaiting I am guessing. There are some pictorial evidence that might suggest mailcollars or collars of scales.

They are portrayed on alaunt and mastiff like hounds and therefore hounds that would have been used for boarbaiting. But I have not seen any mentioning of them in text. As all sorts of hounds could be used in boarhunting, my guess is all kinds of dogs could wear them.

_

_

Leashes

The need of holding on to the dog has been ever present. The leash was mostly of two kinds, the couple and the liam. When the leash was not in use it was commonly hung on the arm, or in some cases the huntinghorn, or tucked into the belt.

♦ Limes

A liam, lyome, or fyame, is an old Word for leash. It could be made of silk or leather, Edward of Norwich informs us that the best lyams are made of White (tanned with fat, tawed) horseleather. The ‘race’ lymer gets its name from being used on a lyme.

In ‘Expenses of Mary’ we read about of ” A lyame of White silk with collar of white vellat embrawdered with perles, the swivell of silver.” ” Dog collors of crymson vellat with vi lyhams of white leather.” ” A Heme of grene and white silke.” ” Three lyames and colors with tirrett of silver”

according to Master of Game: “and the rope of a limer three fathoms and a half, be he ever so wise a limer it sufficeth. The which rope should be made of leather of a horse

skin well tawed. “

A hound was said to carry his liam well when he just kept it at proper tension, not straining it.

♦ Couples

Sometimes the dogs where leashed together two by two. Edward has some smart advice about how a couple should be fashioned: “And also he (the boy who cares for the dogs) should be taught to spin horse hair to make couples for the hounds, which should be made of a horse tail or a mare’s tail, for they are best and last longer than if they were of hemp or of wool. And the length of the hounds’ couples between the hounds should be a foot .” It seems this is mostly used on raches.

Edward has some smart advice about how a couple should be fashioned: “And also he (the boy who cares for the dogs) should be taught to spin horse hair to make couples for the hounds, which should be made of a horse tail or a mare’s tail, for they are best and last longer than if they were of hemp or of wool. And the length of the hounds’ couples between the hounds should be a foot .” It seems this is mostly used on raches.

♦ Ropes

Ordinary ropes, or at least what looks like ropes, is seen quite alot in the illuminations. While it is possible these are made of horsehair, silk and all the other suggestions and recommendations, I find it rather believable that some are of ordinary hemp. As Edwards say that hemp is not as good as the others, it is a indication towards hemprope being used. Linen might of course be used as well, but all that has used linen ropes know how hard a knot is to get loose if it gets wet….

While it is possible these are made of horsehair, silk and all the other suggestions and recommendations, I find it rather believable that some are of ordinary hemp. As Edwards say that hemp is not as good as the others, it is a indication towards hemprope being used. Linen might of course be used as well, but all that has used linen ropes know how hard a knot is to get loose if it gets wet….

_

–

Using the leash and collar

The use of leash and collar is similar to those use today, but there are some tricks of the trade they medieval berner used.

♦ Twisting around the arm

To have the use of the hands free it is common to see Berners twisting the leash around their upper arms a couple of turns, thus gaining the use of the hands to carry things in or handling things with. It keeps the dogs safely secured and even big dogs are rather easy to handle in this way. It is a smart way to keep the use of the hands free while having a leashed hound. This technique also seems popular when you double the leash up.

♦ Coupling up

Often you see dogs, especially Raches coupled up. this was done by putting a leash between two dogs. Coupled up dogs could be gathered up together in a hardle, consisting of 8 dogs. When set on the game they where then usually uncoupled, although one sees still coupled dogs running after prey in illuminations.

“And because a man cannot come nigh him with a lymer, it is good to uncouple the hounds, for the hounds will get nigh them quicker”

There is some thoughts about that a ‘firm’ older dog was coupled with a more inexperienced young dog, hence making a sort of Learning Couples.

♦ Removing the collar

Removing the collar when releasing the hounds seems to be fairly common. You see dogs released on the prey without collars, and also berners (doghandlers) with several collars hanging from their arm. Maybe this was done to lessen the risk of the dog getting caught in the under-brush.

♦ Doubling the rope

Pulling the rope through the ring in the collar and then back to the hand, thus doubling is not that common, but it does exist and it is a very good way to hold a dog when you are about to slip it. It is harder to hold it firm when the dog pulls though as dropping one end of it will make it run trough and the dog bolting. Thus it is mostly used with tying one end to the arm.

Veltrahus from Ucellos ‘the night hunt’ 1470, the leash tied to his arm and doubled through the collar.

–

–

Leash Connection

When you have a leash, and a collar, there comes a point when you need to connect the two to each other. The most common way seems to be to a ring at the collar. This is often attached directly at the collar. Sometimes it is set in the space between the ends of the collar. But the way to connect the rope to this ring or swivel is not always that easy to figure out.

♦ The screw

There is some thoughts about the use of a kind of metalscrew. I have not seen any conclusive evidence on this, and I have read nothing about anything similar. There is, for example a picture in the Luttrel psalter that some say shows this screw-connection, but to be honest, it can just as well show bells on the dogs collars

I decided to make one anyway, just to try if it was actually any good. My experience is that it had a tendency to unscrew, leaving the dog all of a sudden plodding along on its own. This kind of undermines the whole business of leashing the hound. It is also often faster to just tie the rope or remove the collar.

♦ Permanent attachment

There are some illuminations that seems to show that the leash is just permanently attached to the collar. There is no need to actually be able to untie for example a lymer, if it is always held on a leash when out. Also, as it seems fairly common to remove the collar on release the need to remove the leash is little in those cases to.

♦ Tying

Probably the most common, and also the one I found works best. It could be a bit of a bother to get off fast, but if that is not really needed, then it works well. This is the solution I mostly use myself.

–

–

–

Muzzles

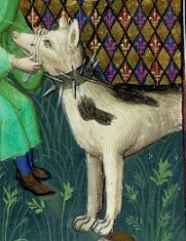

These seems to be of the same type mostly, they all consists of leather straps holding the snout closed. I have seen none that uses a basket over the mouth.

Evidently mostly dogs that might have a tendency to bite had these, alaunts being treated to a muzzled more often.

–

–

The stick

The berner is often shown carrying a stick. Sometimes you are also advised to cut a stick or a switch. This was a stick used to punish and chaste the dog. You beat the dog if it did wrong, or if it did something you wanted it to stop with, for example if you wanted it to stop biting/eating the prey after catch. In Tristan and Isolde they also say they beat the dogs on the paws with hazelswitches to get them excited before the hunt.

The berner is often shown carrying a stick. Sometimes you are also advised to cut a stick or a switch. This was a stick used to punish and chaste the dog. You beat the dog if it did wrong, or if it did something you wanted it to stop with, for example if you wanted it to stop biting/eating the prey after catch. In Tristan and Isolde they also say they beat the dogs on the paws with hazelswitches to get them excited before the hunt.

Beating the dog is a brutal and not very efficient way of training dogs that Exploring the medieval hunt does not condone. It is a savage custom that unfortunately still is used by some. In the medieval days it was an accepted practice though, and even beating the young boys who where serving at the kennels was recommended.

Do not beat your dogs.

–

–

Bear and boar armour

The dogs in armour always provoke the imagination of us modern people to run wild. There is little written proof of the armoured dogs, in the most common huntbooks it is not mentioned at all. There are pictures of it though. We see dogs hunting boars in Spain wearing them and also on tapesteries hunting bear. The use of armour would be when hunting prey that would be dangerous to the dogs, mainly bear and boar. Technically the antlers of a hart would be just as, of not more fatal, but it seems one did not use armour here. This is probably because of the speed-reduction it would impede on the dog during the chase. Boars and bears are not as fast and therefore one could afford swapping speed for protection.

Dog hunting a bear, in the Devonshire hunting tapestry. Possibly in textile armour? Judging from the lines that gives a gambeson like look

–

–

Bells

The use of bells on the collars for the dogs might have been purely decoration, or it had the purpose of making the movements of the dog easier to follow when it is running around.

The bell seems to have been attached either on the collar, or at the end, on the strapend.

Closing words

This article have been browsing the tools of the doghandler. It is our hope it will awaken your slumbering researchspirits and make you throw yourself out into the world looking att stuff. We hope it has pointed out some things one can look at, and maybe help you interpret what you see on pictures and in artefacts on museums.

Even if this article has had quite alot of pictures, there are still more collected in our FB-album. If you like to see more pictures of dogs and doghandling tools, I recommend that. You find it here

If you like to see recreated dogcollars we made, you can find them in our other FB-album; here

/Johan